|

|

|

Charles Rennie Mackintosh

Combining a progressive modernity with the spirit of romanticism, the Scottish architect and designer Charles Rennie Mackintosh (1868-1928) created many of the best loved and most influential buildings, furniture and decorative schemes of the early 20th century.

Few designers can claim to have created a unique and individual style that is so instantly recognisable. Famous today as a designer of chairs, Charles Rennie Mackintosh (1868-1928) was an architect who designed schools, offices, churches, tearooms and homes, an interior designer and decorator, an exhibition designer, a designer of furniture, metalwork, textiles and stained glass and, in his latter years, a watercolourist.

|

|

| Excelling in all these areas, Mackintosh left hundreds of designs and a rich volume of realised work. His distinctive style mixed together elements of the Scottish vernacular and the English Arts and Crafts tradition with the organic forms of Art Nouveau and a drive to be modern. As his work matured Mackintosh employed bolder geometric forms in place of organic-inspired symbolic decoration. |

|

|

| Charles Rennie Mackintosh’s work can be divided into three main areas: public buildings, private homes and tea rooms. The Glasgow tea rooms he designed in the early 1900s are perhaps his most unique contribution in which art, architecture and design came together in a complete environment. These light, elegant and sophisticated interiors were an enormous contrast to the gritty, smoky urban city of Glasgow where he was born, trained and lived for most of his adult life. Glasgow is where the majority of his work was executed and Mackintosh’s career paralleled the city’s economic boom. By the end of the 19th century Glasgow was a wealthy, burgeoning European city with an immense network of trade and manufacture that supplied the world with coal and ships. It was also a rich source of commissions for a gifted young architect and designer. |

|

|

One of eleven children, Mackintosh was born in 1868 to Margaret and William Mackintosh, a clerk in the police force. He grew up in Glasgow and from the age of nine attended the Allan Glen’s Institution, a private school for the children of tradesmen and artisans, which specialised in vocational training. At fifteen Mackintosh began evening classes at Glasgow School of Art and a year later, in 1884, he began a five-year pupilage with the Glasgow architects John Hutchins. In 1889 he joined the more eminent firm of Honeyman & Keppie, where he received a traditional Beaux Arts training typical of the perio |

|

The 1890s was a decade of learning and development for Mackintosh, when he continued his architectural training, travelled to Italy, attended and gave lectures, and formed new friendships. These experiences widened his interest in architecture to include the fine and decorative arts, and caused Mackintosh to align himself firmly with the progressive school. Among his friends were Francis Newbery, the inspirational director of Glasgow School of Art and his wife Jessie, Herbert McNair, a fellow draughtsman at Honeyman & Keppie and the sisters Margaret and Frances Macdonald, who attended Glasgow School of Art.

Mackintosh, McNair and the Macdonald sisters came to be known as The Four. Together they designed and exhibited work including posters and furniture. Through them, Mackintosh was introduced to the broader field of art and in particular to the feminine, symbolic graphic style of the Macdonald sisters. In 1894 they were described by the press as “the Spook School”, a reference to their elongated, sinuous and feminine graphic forms based on fabled and mythic themes. Mackintosh married Margaret Macdonald in 1900 and she was to remain his principal collaborator throughout his life. |

|

|

In 1896 Francis Newbery invited twelve local architects to enter a competition to design a new building for Glasgow School of Art. One of these firms was Honeyman & Keppie, which was almost certainly selected because of Mackintosh’s friendship with Newbery. Honeyman & Keppie won the competition with Mackintosh as designer. This, his first and most important commission, was to seal his future reputation. |

|

| The brief for the building of Glasgow School of Art on a steeply sloping site with an extremely tight budget was simple, utilitarian even. Due to the financial restrictions the design was completed in two phases. The north end opened in 1899, but the construction of the west end did not start until 1907 and was only completed in 1909. This time lapse coincided with the most productive period of Mackintosh’s career and accounted for the changes in style between the first and second phases. The later west end is not only much more radical and progressive than the north end, but Mackintosh also added an attic storey to create more studio space. |

|

| The School forms a simple E-shaped building with an austere and asymmetrical north façade with massive studio windows. A single central entrance leads to a staircase with two floors of studios to the right and left. The bright and airy Director’s Office with fitted cupboards and a fireplace is directly above the entrance. At the centre of the school, at the top of the stairwell top-lit with a glazed roof and timber trusses like a medieval barn, is an exhibition space called the Museum. There was little additional decoration to the building because of the limited budget. Unusually for the period there was only a small stone carving over the entrance and any decoration that Mackintosh managed to incorporate was functional as well as beautiful. The massive fenestration of the north façade is visually broken up by decorative wrought-iron brackets that brace the huge windows and can be used as window cleaning supports. The lively wrought-iron railings also give decoration to an otherwise reduced building with finials of stylised birds, bees and beetles that resemble Japanese Mon or family crests. |

|

|

In the second phase of construction, the west elevation was radically altered with the addition of the library’s dramatic three-storey windows. The interior of the library is no less surprising, with the central fall of light from the windows contrasting with the dark stained wooden gallery supported by split beams. Mackintosh designed the fittings and furnishings in dark stained wood decorated with splashes of red, green and white – a magical mix of academic sobriety and modern geometric intensity. This library was probably one of Mackintosh’s most exciting interiors in a building that both kick started his architectural career and later revealed his mature style.

Mackintosh’s other domestic schemes ranged from single rooms, such as the music room he designed in Vienna for Fritz Wärndorfer in 1902, to the interiors of existing buildings, like his 1904 scheme for the 18th century Hous’hill owned by Kate Cranston and her husband John Cochrane. Yet his most important house was Hill House on a hillside site on the outskirts of Helensburgh overlooking the Clyde estuary. Mackintosh secured the commission after showing his client – the publisher Walter Blackie – Windyhill, the house that he built for his friend William Davidson in Kilmacalm in 1901.

The following year Mackintosh started work on Hill House by submitting the internal layout to Blackie for approval, before designing the elevations which reflected the function of the interior. A narrow building running from east to west with all the major rooms looking south over the estuary, Hill House was foremost a practical family home with the library off the main hall designed for receiving clients and the nursery situated at the furthest end in the north extension where the kitchen, services and children’s rooms were housed.

Mackintosh used local sandstone and plain roughcast rendered or harled walls. Features such as the massive chimney and staircase tower – which came from the Scottish baronial tradition – were combined with a modern visual vocabulary, such as the flat roof of the sun lounge. Mackintosh was allowed a free rein with the decoration of the hall, sitting room and bedroom, where he designed everything from built-in wardrobes to firetongs and pokers. His desire to create a total environment was in keeping with the artistic taste of the time. Josef Hoffmann in Vienna and C.F.A Voysey and M.H Baillie Scott in England also designed not only buildings but furniture and furnishings too. The Hill House is perhaps Mackintosh’s most polished interior since he experimented with – and fine tuned – his aesthetic not only with the Windyhill commission, but also with his own homes at 120 Mains Street and then at 78 Southpark Avenue, Glasgow. At Mains Street in 1900, in collaboration with his wife Margaret, Mackintosh installed his first all-white sitting room and experimented with the contrast of light and dark rooms and ‘male’ and ‘female’ environments.

Mackintosh was extremely fortunate to work throughout his career with clients such as Walter Blackie, who allowed him to have complete control over a project. However his most supportive client – and most generous and constant patron – was Miss Catherine Cranston, who owned and ran a chain of Glasgow tea rooms. At the time Glasgow tea rooms were unique as places where people of different classes could meet friends, relax and enjoy non-alcoholic refreshments in a variety of spaces within the same building. At a time when the temperance movement was increasingly popular, tea rooms like Miss Cranston’s played an important role in Glasgow life.

Mackintosh was first employed by Miss Cranston in 1896 to provide a stencil decoration for the walls of her tea rooms at 91-93 Buchanan Street. These rooms had been built and refurbished by George Washington Brown of Edinburgh, with George Walton overseeing the decoration and providing the furniture. Mackintosh was asked to create a wall decoration for the ladies’ tea room, the luncheon room and the smokers’ gallery. His frieze depicted elongated female figures in pairs facing each other surrounded by roses. This commission led to others for Miss Cranston from 1898 to 1899 when Mackintosh had sole responsibility for the Argyle Street tea room. For this, his first major commission for furniture, he designed his first high-backed chair. In 1900 he designed the ladies’ luncheon room and related rooms for Miss Cranston’s Ingram Street tea rooms and in 1903 the Willow tea rooms.

The Willow tea rooms occupied a narrow site on Sauchiehall Street – old Scots for ‘alley of willows’, hence the use of willow for many of the decorative motifs used. Nothing escaped Mackintosh’s attention. He and Margaret designed everything from furniture and menus, to the waitresses’ uniforms. Within the four storey building, Mackintosh created a ladies’ tea room on the ground floor, with a general lunch room at the back and a tea gallery above it. On the first floor was a more exclusive ladies’ room with a men’s billiard and smoking room on the floor above. The most extravagant of the rooms was the Room de Luxe on the first floor. Overlooking the street, it had white walls with a frieze of coloured glass, mirrored glass and decorative leading, a gesso panel by Margaret Macdonald, splendid double doors with further leaded glass decoration and silver painted high-backed chairs and sofas upholstered in rich purple.

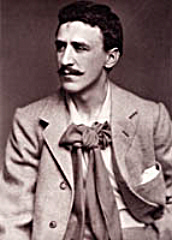

In 1914 Mackintosh left Honeyman & Keppie – and Glasgow – for reasons which have now been lost. This is the period of his life that, over time, has been elaborated to create the image of a tragic romantic hero who was rejected by his home town, and that so fits with the famous portrait of Mackintosh with a moustache and a bow tied at his neck. It has been written that he left Honeyman & Keppie because he had been drinking heavily, which was supposedly due to his difficult temperament and his inability to attract new clients. It is possible that he intended to move to Vienna, where he was highly respected having forged friendships with Austrian architects such as Josef Hoffmann and Koloman Moser, only for his plans to be thwarted by the outbreak of World War 1. Mackintosh moved to Walberswick in Suffolk in 1914, where he produced a series of botanical watercolours. While there he was arrested as a spy, possibly because he received post from central Europe, and he then moved to London.

Mackintosh tried to gain work to establish himself in England with the status he had enjoyed in Glasgow, but at a time when classical architecture was increasingly popular his style seemed outmoded. There is also little doubt that he was demanding to work with and needed exceptional clients who were able to give him the free range he required. However, Mackintosh did produce fabric designs for Messrs. Foxton and Messrs. Sefton of London and in 1916 he received a commission to refurbish and decorate a house at Derngate in Northampton for W.J. Bassett-Lowke, which he executed in a very modern style, similar to that of the Library at Glasgow School of Art. Bereft of opportunities – or possibly the ability – to build, Mackintosh created a remarkable series of watercolour paintings during the 1920s.

An endlessly fascinating man who created work with a very distinctive voice, Mackintosh emerged from the Arts and Crafts period as an urban architect who became progressively less interested in its rural aesthetic and increasingly inspired by the progressive art movements of Germany and Austria. In 1923 he moved to southern France where he spent the last five years of his life before dying in London. Despite the disappointments of his later years, his early and mid-career work in Glasgow – much of which is still in use today – has sealed his reputation as one of the most important architects and designers of the turn of the 20th century.

|

|

|

|